Everyone knows the story of Noah and the great flood of The

Bible, or at least they think they do. Stories

like this one and many others that have permeated the social sphere are usually

not remembered, recited or quoted with accuracy or even with any of the

relevant context to the scriptures that surrounds them. Instead, these tales have

become a kind of cultural meme, and in the case of “Noah” over time the myth has been

whittled down to the iconography of animals, rainbows and a big wooden boat.

New

York filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, most well-known for his bleakly-pitched,

visceral indie work like “Requiem for a Dream” and “Black Swan”, cares nothing

about the memetic simplicity or even the moral dichotomies within the Noah

story of the original biblical text.

With his recent adaptation—working within a much bigger budget than he’s

usually afforded—he transgresses the familiar narrative in search for the

darker implications of the legend.

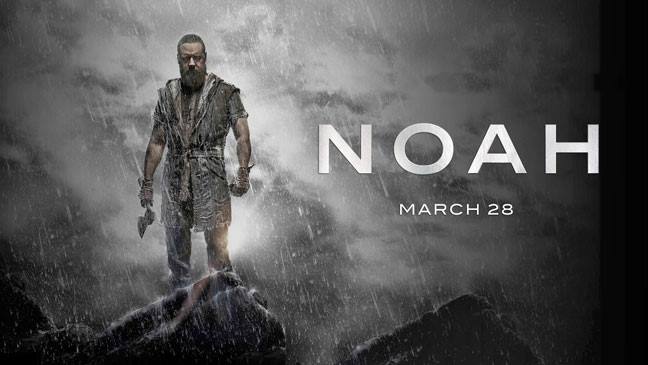

In this

alternative universe version of “Noah” , Russell Crowe plays our hero as he is

shown by the creator visions of a watery apocalypse that will destroy every

living person in the world. His grandfather Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins)

informs him that he has been called to save his family and the animalia of the

planet by building a large ark that will float along the earth’s surface during

the imminent flood. (Yeah yeah yeah—we know all that.) However, this time

around, what Noah isn’t telling his family is that perhaps the creator never

intended for the human race to survive past their death once they have saved

the other species. This becomes even

more complicated when Noah’s adopted daughter Ila (Emma Watson) is struggling

to bare children with his eldest son Shem (Douglas Booth), while at the same time his younger

son Ham (Logan Lerman) is begging for a wife to validate his budding

manhood.

Much

has been written about the fundamentalist reaction against Aronofsky’s

additions to the source material, and it’s obvious within the first ten minutes

that accuracy is not his aim. Much of the movie’s second half deals with the

existential angst that these characters have to endure in the face of their

seemingly elusive deity. Noah is forced to ponder if he was chosen because he’s

the best of mankind or simply the best man for the job. The psychological

weight this brings down on him and his family when they hear the screams outside

of the arch as the flood rises around them exemplifies the universal truth of

moral and spiritual uncertainty that this adaptation is interested in. The disgruntled faithful should know that, as

a story, the slanting of the text to better examine these characters and to give

these actors more pathos to deal with is not where the movie fails…but this does

lead me to my other point: rock monsters.

Maybe

in a grand statement of defiance, or perhaps in a broad brushstroke of creative

freedom, Aronofsky includes many Tolkien fantasy elements that unfortunately overpower

the first half of this otherwise dark film with misjudged silliness. But besides

scene-ruining rock monsters, Hopkins’ wizard-like Methuselah seems to serve more

as a writing device than as a character, telling us what we already know or could

gather from the plot, handing out magic-grow tree-seeds, and going on and on about

berries. Luckily the power and paranoia of the second

half just barely saves the film from the Dungeons and Dragons nonsense of the

first half.

I see

no reason why details about the rather short biblical verses shouldn’t be

altered for the sake of exploring characters and situations in a more complex

or subversive way, even if the film’s pot boils over with too many discordant

ideas from time to time. “Noah” is, without a doubt, an audacious and deeply

melancholy cinematic experience, but it may alienate fans of the book.

Originally published in the Idaho State Journal/March-2014

No comments:

Post a Comment